This script was primarily used by the priestly class, datu, for the creation of magical texts and calendars. Early accounts by observers claim that literacy was widespread and taught from person to person rather than in a formal school setting. (Kozok, 36-37) Most collections of physical scripts are incomplete, damaged, and poorly preserved. Also, over 90 percent of Batak texts are located overseas. (Kozok; Cummings, 275)

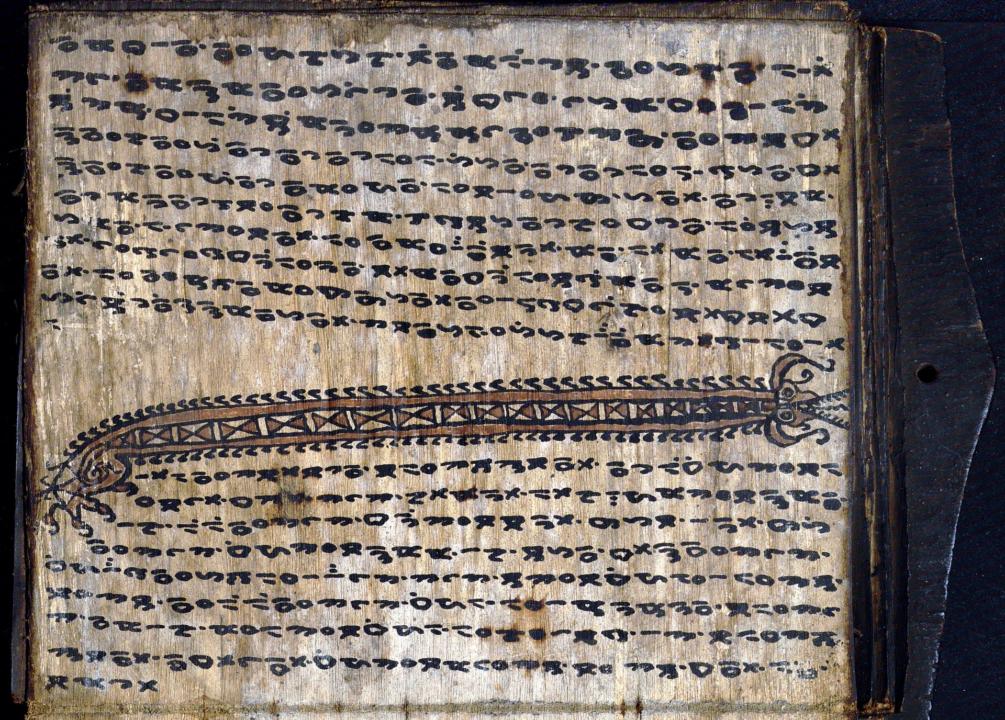

Batak scripts were accumulated into books known as pustaha and “were [primarily] written on long strips of bark from the Aquilaria tree. Pustaha are significant because they contain information on the performance of rituals and the interpretation of omens, as well as formulas to be used in the manufacture of medicines. (Kozok 34)” Batak scripts written on bamboo, bone and paper. “Of the bamboo scripts, 50% comprise laments and letters, and thus are not written by specialists, or datu, but by non-professional literates. This clearly suggests that literacy must have been much more widespread than is generally assumed... ”When reading texts, all Batak have the strange habit of pronouncing the vowels in a very long-drawn [...] and singsong way, while appearing to be lost in deep reflection. It seems almost impossible for them to read quietly and silently to themselves; on the whole, the proceedings are very slow. (Junghuhn 1847/:260.)“ (Kozok, 48.)”

The complexity of the rituals, customs, and widespread usage of this writing system denote that this system has existed far longer than the earliest attested date listed above. However, many of the sources available regarding the Batak script are not written in English, making it difficult for this researcher to ascertain a specific date and location for this script's origin.